Notes for a deja vu

Manifesto Colectivo los Ingrávidos

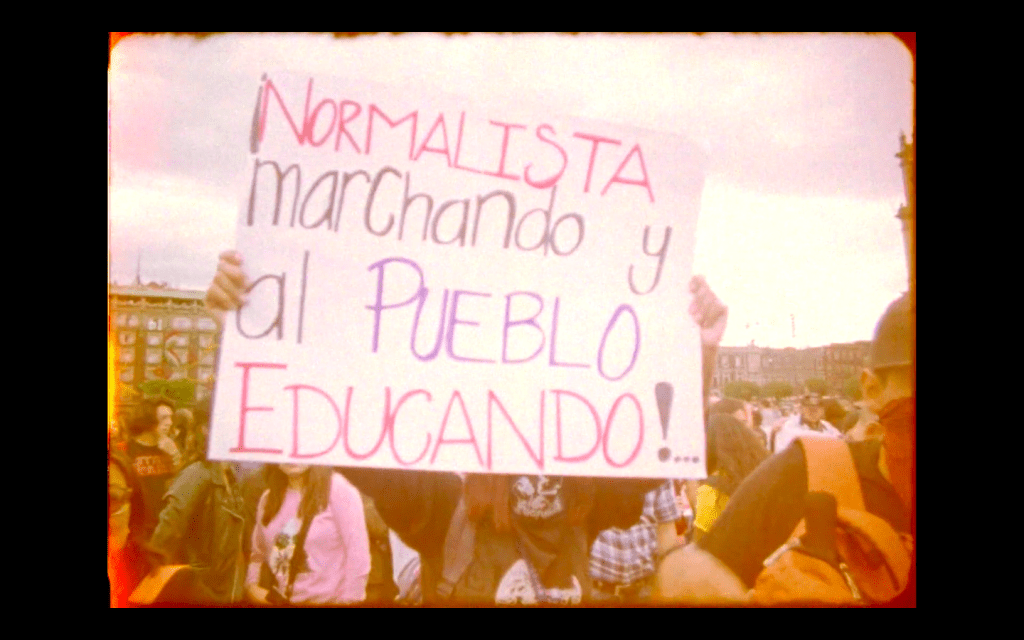

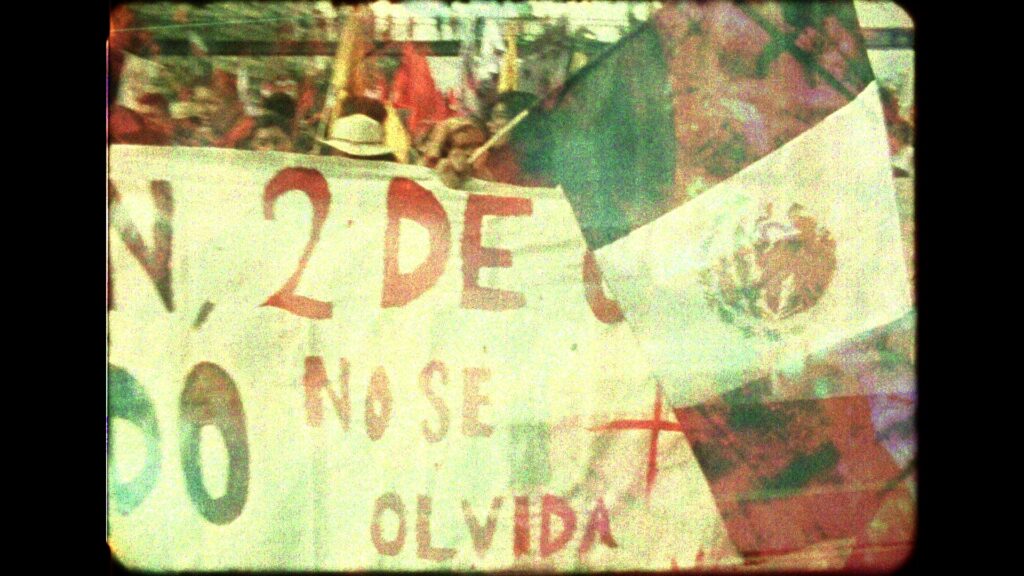

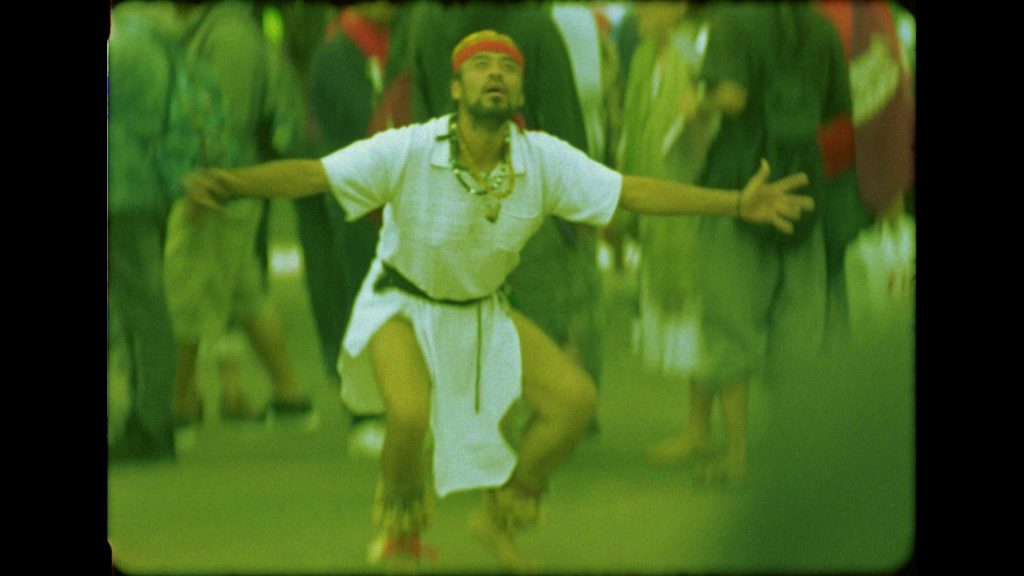

The television empire ideologically resolves its contradictions through a huge propaganda machinery. The “neutral” aesthetisation of immediacy is the procedure generalized by Televisa to formulate and promote a “self-consistent”, totalitarian and “traditional” image. What means do we posses to unmask the transfer and concealment of the conflicts and contradictions implied by the “neutralized” immediacy?

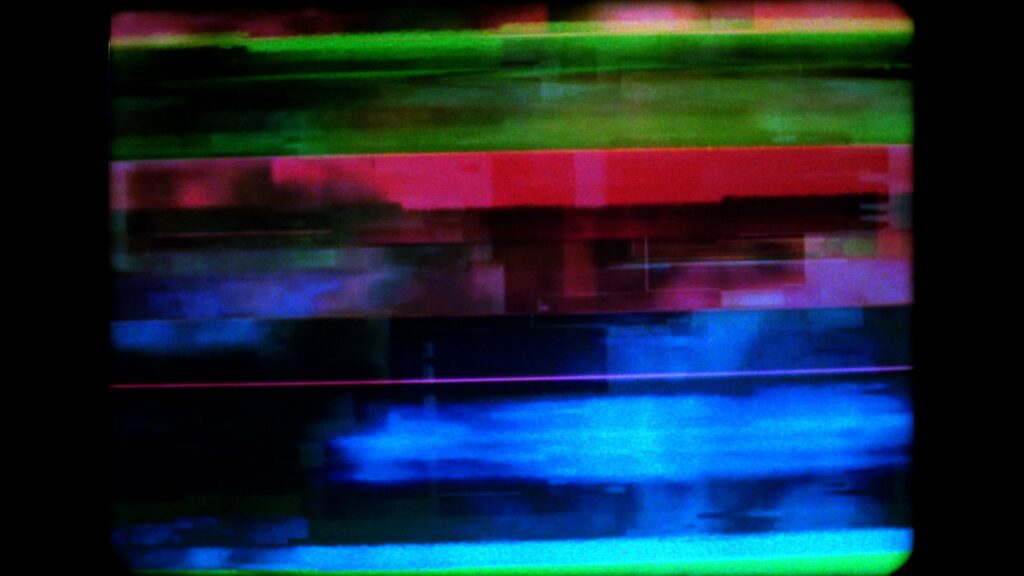

We summon thus to the ostensible degradation of televised communication. Make any message, “original” or “traditional”, inoperative through the induction of diverse semiotics. Destitute the sense of its discourse by intervening the grammar of its language, inoculate de-comprehension, the stutter and the echolalia. Make the preferable content that its tirade would communicate illegible.

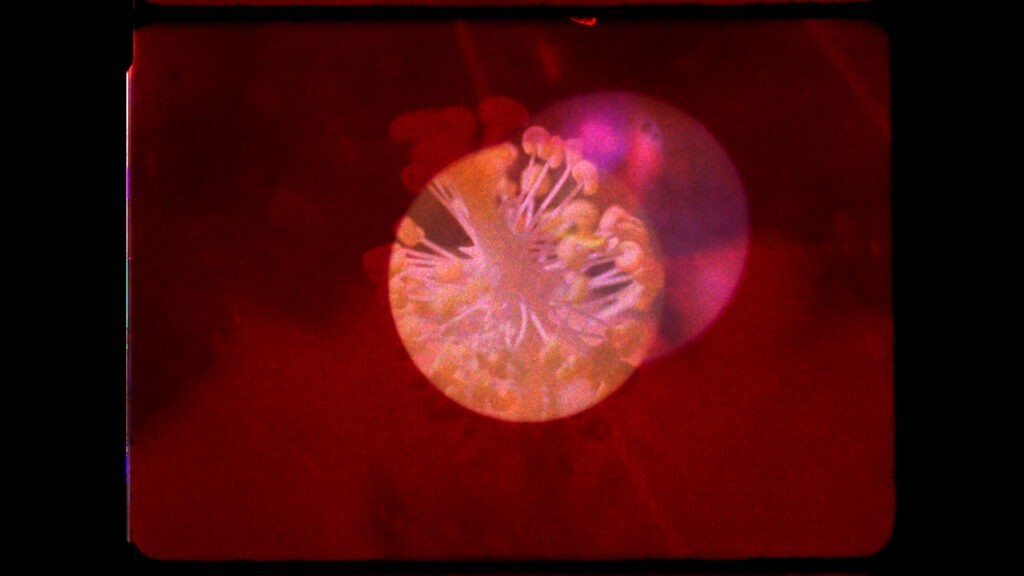

A generalized aesthetics to unhinge:

We have to destroy the pseudo-poetry, all of it foundered, that the television empire claims.

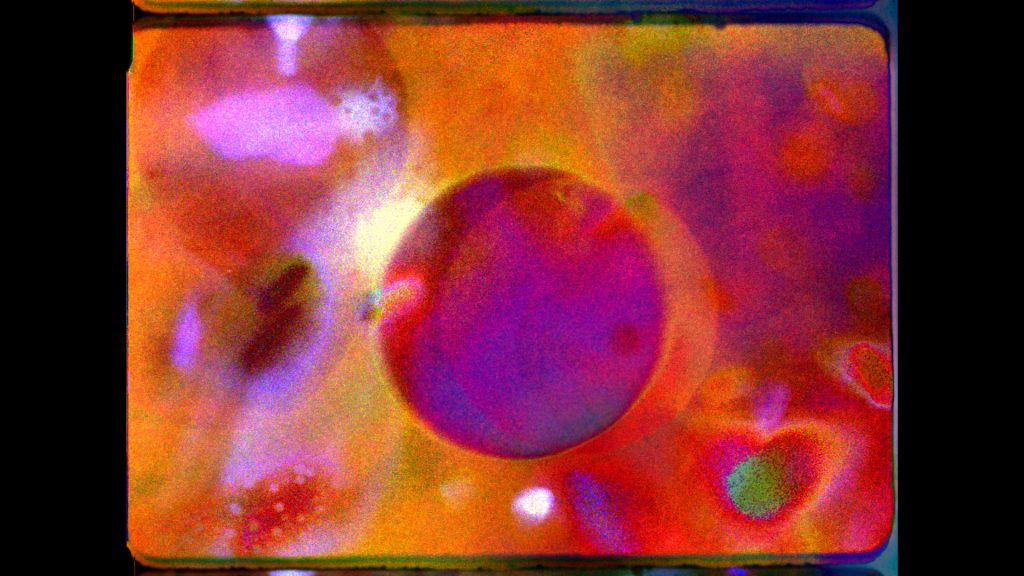

We have to destroy the rhythm of its vacuous slow motions.

We have to destroy the horrendous clarity of their million-dollar cameras. We have to syncopate and de-phase.

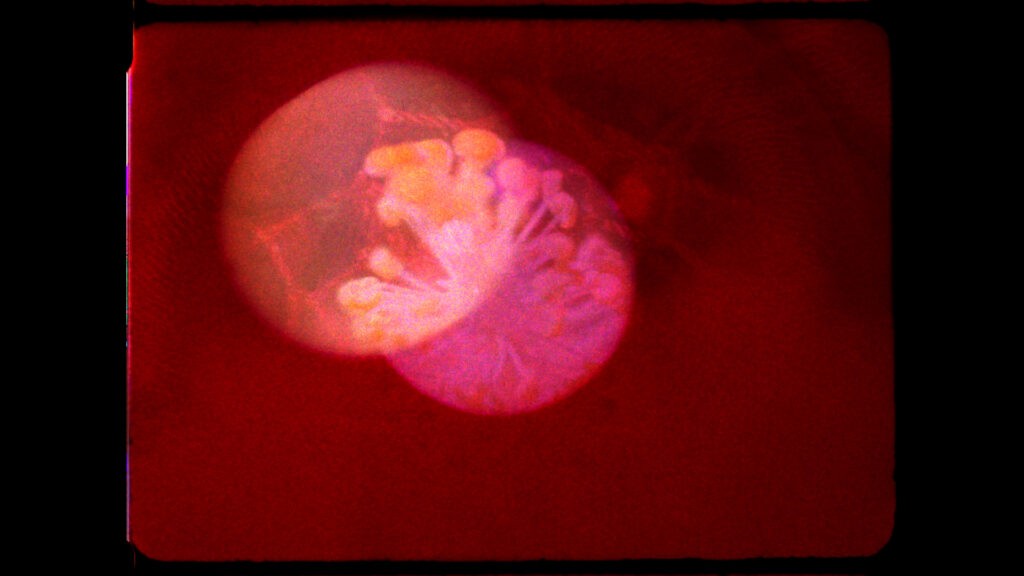

We have to superimpose the sick eye that supports its colorimetry.

We have to turn its millionaire propaganda into noise.

We have to submit the audiovisual grammar of Televisa traditions to continuous destruction.

We have to demolish the neutralized immediacy that the frivolous romanticism of its images invokes.

We have to pose the systematic de(re)connection of the images and sounds.

“When the governments invade us with their grand machinery of bureaucracy, war and mass media, we feel like the only means of preservation is by animating our sense of rebellion and disobedience, even if we have to pay the price of mere anarchy and nihilism. All public ideologies, values and ways of life must be brought into question, attacked.” Jonas Mekas

Colectivo Los ingrávidos, 2012

The First Statement of the New American Cinema Group

In the course of the past three years we have been witnessing the spontaneous growth of a new generation of film makers—the Free Cinema in England, the Nouvelle Vague in France, the young movements in Poland, Italy, and Russia, and, in this country, the work of Lionel Rogosin, John Cassavetes, Alfred Leslie, Robert Frank, Edward Bland, Bert Stern and the Sanders brothers.

The official cinema all over the world is running out of breath. It is morally corrupt, esthetically obsolete, thematically superficial, temperamentally boring. Even the seemingly worthwhile films, those that lay claim to high moral and esthetic standards and have been accepted as such by critics and the public alike, reveal the decay of the Product Film. The very slickness of their execution has become a perversion covering the falsity of their themes, their lack of sensibility, their lack of style.

If the New American Cinema has until now been an unconscious and sporadic manifestation, we feel the time has come to join together. There are many of us—the movement is reaching significant proportions—and we know what needs to be destroyed and what we stand for.

As in the other arts in America today—painting, poetry, sculpture, theatre, where fresh winds have been blowing for the last few years—our rebellion against the old, official, corrupt and pretentious is primarily an ethical one. We are concerned with Man [sic]. We are concerned with what is happening to Man [sic]. We are not an esthetic school that constricts the filmmaker within a set of dead principles. We feel we cannot trust any classical principles either in art or life.

1. We believe that cinema is indivisibly a personal expression. We therefore reject the interference of producers, distributors and investors until our work is ready to be projected on the screen.

2. We reject censorship. We never signed any censorship laws. Neither do we accept such relics as film licensing. No book, play or poem—no piece of music needs a license from anybody. We will take legal action against licensing and censorship of films, including that of the U.S. Customs Bureau. Films have the right to travel from country to country free of censors and the bureaucrats’ scissors. United States should take the lead in initiating the program of free passage of films from country to country.

Who are the censors? Who chooses them and what are their qualifications? What’s the legal basis for censorship? These are the questions which need answers.

3. We are seeking new forms of financing, working towards a reorganization of film investing methods, setting up the basis for a free film industry. A number of discriminating investors have already placed money in Shadows, Pull My Daisy, The Sin of Jesus, Don Peyote, The Connection, Guns of the Trees. These investments have been made on a limited partnership basis as has been customary in the financing of Broadway plays. A number of theatrical investors have entered the field of low budget film production on the East Coast.

4. The New American Cinema is abolishing the Budget Myth, proving that good, internationally marketable films can be made on a budget of $25,000 to $200,000. Shadows, Pull My Daisy, The Little Fugitive prove it. Our realistic budgets give us freedom from stars, studios, and producers. The film maker is his own producer, and paradoxically, low budget films give a higher return margin than big budget films.

The low budget is not a purely commercial consideration. It goes with our ethical and esthetic beliefs, directly connected with the things we want to say, and the way we want to say them.

5. We’ll take a stand against the present distribution—exhibition policies. There is something decidedly wrong with the whole system of film exhibition; it is time to blow the whole thing up. It’s not the audience that prevents films like Shadows or Come Back, Africa from being seen but the distributors and theatre owners. It is a sad fact that our films first have to open in London, Paris or Tokyo before they can reach our own theatres.

6. We plan to establish our own cooperative distribution center. This task has been entrusted to Emile de Antonio, our charter member. The New York Theatre, The Bleecker St. Cinema, Art Overbrook Theatre (Philadelphia) are the first movie houses to join us by pledging to exhibit our films. Together with the cooperative distribution center, we will start a publicity campaign preparing the climate for the New Cinema in other cities. The American Federation of Film Societies will be of great assistance in this work.

7. It’s about time the East Coast had its own film festival, one that would serve as a meeting place for the New Cinema from all over the world. The purely commercial distributors will never do justice to cinema. The best of the Italian, Polish, Japanese, and a great part of the modern French cinema is completely unknown in this country. Such a festival will bring these films to the attention of exhibitors and the public.

8. While we fully understand the purposes and interests of Unions, we find it unjust that demands made on the independent work, budgeted at $25,000 (most of which is deferred), are the same as those made on a $1,000,000 movie. We shall meet with the unions to work out more reasonable methods, similar to those existing off-Broadway—a system based on the size and nature of the production.

9. We pledge to put aside a certain percentage of our film profits so as to build up a fund that would be used to help our members finish films or stand as a guarantor for the laboratories.

In joining together, we want to make it clear that there is one basic difference between our group and organizations such as United Artists. We are not joining together to make money. We are joining together to make films. We are joining together to build the New American Cinema. And we are going to do it together with the rest of America, together with the rest of our generation. Common beliefs, common knowledge, common anger and impatience binds us together—and it also binds us together with the New Cinema movements of the rest of the world. Our colleagues in France, Italy, Russia, Poland or England can depend on our determination. As they, we have had enough of the Big Lie in life and the arts. As they, we are not only for the new cinema: we are also for the New Man [sic]. As they, we are for art, but not at the expense of life. We don’t want false, polished, slick films—we prefer them rough, unpolished, but alive; we don’t want rosy films—we want them the color of blood.

September 30, 1962